You can call it whatever you want, but for two hundred years, the Unitarian branch of our tradition, particularly, has floated in a sea of white supremacy culture. This should not surprise us, because white America in general has only come to question our own racism over the last couple of generations.

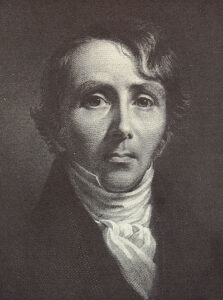

Rev. William Ellery Channingonly come to question its own racism during the last couple of generations.

Some of our brightest lights, Ralph Waldo Emerson included, were as racist as could be. To be intelligent and erudite is not to be socially perceptive.

But we can start before Emerson. William Ellery Channing is not well known today, but his was a name to conjure with two hundred years ago. His 1819 sermon, “Unitarian Christianity,” lays out the classic, Christian Unitarianism of the early nineteenth century. It was seen as religiously radical at the time. Scratch many a liberal Christian today, though, and Channing’s old sermon resonates in theme if not in name.

For thirty years Channing was renowned, not only as senior minister at Boston’s prestigious Federal Street Church, but as a prominent lecturer, writer, and what we would today call a “public intellectual.” Unitarian Universalist historian David Robinson describes him as “the single most important figure in the history of American Unitarianism.”

And Channing knew it. He opined publicly on topics ranging from theology, to history, to what we now call sociology, to proper living and personal development, to slavery and abolition. Slavery had caused tension and infighting since before the Declaration of Independence. Channing died long before the controversy erupted into Civil War. But it was much in his thoughts.

He came from prosperous, influential New England stock. His grandfather had signed the Declaration of Independence. Growing up in Rhode Island, his family owned slaves. Later, tutoring in Virginia as a young man and then visiting the West Indies in mid-life, he got a glimpse of the brutality of plantation slavery. As the “Tapestry of Faith” Adult Religious Education section on Channing puts it, “What he saw sickened him.” His response was ambiguous, however. “Channing was slow to speak out on slavery.”

After a lengthy exchange of letters and conversations with abolitionists and colleagues, he finally wrote an entire book on the subject in 1835. Titled Slavery, it’s rarely read today, even among Unitarian Universalists. Unlike some of his other works, it has not aged well.

Despite any horrors he might have witnessed in Virginia or the West Indies, his opposition to slavery was largely philosophical. Religiously, he declared, it wasn’t right to enslave people. More particularly, to work for someone who was not paying you for your labor was degrading not just to the slave, but to the master. Slavery was, therefore, an affront to the humanity of both.

Possibly because of his childhood experience with slave owning, though. Channing’s book largely accepts comforting stereotypes slave owners put forth to justify the practice. For example, on the cruelty of slavery, he wrote, “Thanks to God, Christianity has not entered the world in vain. . . . It has mitigated bad institutions. There is [in this country] an increasing disposition to multiply the comforts of slaves, and for this let us rejoice.”

Then he added, “The African is so affectionate, imitative, and docile, that. . . he catches much that is good; and accordingly the influence of a wise and kind master will be seen in the very countenance and bearing of his slaves.” One suspects this moth-eaten assumption comes from the smiling black household help of Channing’s childhood. But like a black man accosted by police today, such smiles were hardly expressions of happiness, or even friendship. It was a survival mechanism. Slaves knew better than to let their “owners” know what they were really thinking.

I had to struggle to get through Slavery. While I was reading it, I ran across a magazine article on the discovery and archaeological excavation of a slave cemetery in lower Manhattan. It’s now known as African Burial Ground National Monument. Its history, discovery, and reluctant archaeology—spurred only by continued prompting by New York’s Black community, is itself a study in institutional cluelessness and the need to listen to marginalized voices. Slaves’ skeletons show evidence of serious malnutrition, lack of medical care, constant overwork, and harsh punishment. More than half the remains were of children twelve years old or younger. I have to wonder what Channing would say today if shown such evidence? As with German citizens when Dachau Concentration Camp was opened, would his response be “I just didn’t know?”

Even in the—supposedly—benign North, the average slave died or was killed before even reaching early adulthood! Put beside this harsh reality, I found Channing’s intellectualizing on benevolent slave owners—more harmed by the practice than their slaves—gag-inducing.

Born and married into wealth and privilege, Channing plainly related to slave-owning congregants and associates, rather than what transpired on fields, docks, and warehouses—or even what lay behind those outward smiles of household slaves. This recalls to me the famous James Baldwin quote from the 1960’s, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in rage almost all the time.” How much more must that have been the case when the Black person was actual property, Yet Channing plainly never suspected.

Channing’s “reasonable”—to him—assessment never engaged slavery’s spirit-withering reality. He could assume slave owners were kindly, decent folk. The ones he knew were nice enough to him. This would hold even on plantations.

As one example, Confederate General Robert E. Lee was viewed practically as a saint after the Civil War, by southerners and northerners alike. But Lee did not hesitate to beat slaves ferociously if they failed to toe the line. Writing about slavery after the war, Lee did grant that it was an evil—but that it was “a greater evil to the white man than to the black race.” That was a common rationale among slave owners, one which Channing accepted without question.

Product of his time and class that he was, Channing wanted to be “fair” to everyone. He didn’t want to see slave owners cheated out of their “property.” Nor did he want to see slaves freed too soon, before, he worried, they were ready for the burdens of freedom.

Channing’s analysis of slavery might have been intellectual, but his reaction to abolitionists came right from the gut. He didn’t like them at all. To him, abolitionists, such as fellow Unitarian William Lloyd Garrison, did more harm than good. Channing considered them unreasonable, one-sided, and intemperate. He believed that only slave owners could end slavery, which, he wrote, they were certain to do as soon as they realized how bad the practice was for them, not just the slaves. (Slavery continued for another generation after Channing wrote his book, and was only ended by the Civil War.)

And again, half the skeletons in that slave cemetery were children, dead before the age of twelve years.

Yet Channing was in no way a coldhearted man. Rather, he was a wellspring of real compassion and integrity. Reading his works, his earnestness and regard for people of all conditions are undeniable.

But he was also a walking definition of ahnungslosigkeit—cluelessness: the person of power and privilege who cannot imagine the circumstances of those totally without power or privilege. Yet he never begins to guess how little he actually knows. In Channing, the two elements of cluelessness were richly manifest: failure to understand the other person’s experience, compounded by failure to even suspect one’s own lack of understanding. Renowned public intellectual that he was, Channing plainly did not imagine that an abolitionist, much less an uneducated slave, could tell him anything significant about slavery he didn’t already know.

He was similarly naive when it came to the lives of white laborers in his own Boston. As a prominent speaker and proponent of self improvement, he was engaged in 1840 to deliver a series of lectures on what he termed “self-culture” to a guild of factory workers. He assured them that while their time and means might be limited, they could still read books and magazines, perhaps take up music. There were always ways to take up a contemplative life. Orestes Brownson, a ministerial colleague of more humble origins, acidly observed that this was assuming a lot about men who didn’t know how to read, who had to work sixteen hours a day, six days a week, just to put bread on the table.

It’s easy, of course, to pass judgment on Channing from the vantage point of two centuries later. More challenging is to see his cluelessness reflected in myself—in ourselves—to ponder the times I, for one, have found myself no less ridiculous than the cartoon character, Wile E. Coyote, after he has run off the cliff’s edge, just before he looks down and then starts to fall. The only thing that will keep me from looking as silly as William Ellery Channing, two hundred years hence, will be that his writings were preserved as evidence.

Which brings us to philosopher and essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson, who was coming into prominence just as Channing’s life was drawing to a close. Trained as a Unitarian minister, Emerson rejected the week-in, week-out stress of ministry. He left the parish, and became a famous essayist and lecturer, a leading light in the American Transcendentalist movement, and has been called the father of American individualism. His writings inspired the brash confidence of this nation’s westward expansion.

The real genius and spirituality of his writing can fill the soul even today. In our own time, numerous Unitarian Universalist ministers and scholars look on Emerson as the next best thing to a Unitarian Universalist saint.

In a fascinating book, The History of White People, however, historian Nell Irvin Painter also terms Emerson “the philosopher king of American white race theory.” Unlike Emerson’s other writings, his books and essays on race are largely forgotten today. They put stained context around his brilliant image. Emerson accepted contemporary European racial theories without question, refined them for American eyes, and added a strong racial component to Euro-Americans’ heady belief in Manifest Destiny.

Like Channing, Emerson would have considered himself an ally to slaves. He roundly denounced the practice of slavery, and he rejoiced when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. That didn’t mean he considered the “races” equal, though, or close to it. He was comprehensively racist. He even considered my own Irish forbears an inferior race. That is, along with immigrants from eastern Europe, we Irish were “guano races.” Guano, for the record, is the excrement of sea birds.

To dive into Painter’s thesis: from ancient Rome on, Europeans wrote about their different tribal cultures in racial terms. Different writers from different regions would list reasons why their own group had the most desirable “racial” characteristics. In fact, the very reason the word, “Caucasian” came into use, to designate White people, was that an eighteenth century German, J.F. Blumenbach, wanted to include the Sanskrit-writing Indo-European language group in the so-called “White” race. The Caucasus Mountains were centrally located, distant enough from black African “Negroes” and brown Asian “Orientals” to provide an excuse to connect Europeans and Sanskrit writers in the same “racial” context, while excluding the others. Hence, “Caucasians.” The term was based on language and geography, not at all on biology. Or even skin color. But it caught on. Painter points out that racial theories have nothing at all to do with science, sound scholarship, or even any consistent form of logic.

That didn’t stop Ralph Waldo Emerson from diving in head first. He considered England racially superior to other nations. To him, our English roots were the reason for American racial superiority. There were, he wrote, three races in the British Isles: Celtic, Nordic, and Anglo-Saxon. Americans despised Irish immigrants in Emerson’s time. The Irish were seen as Celtic. So he wrote that Celts were definitely inferior.

Anglo-Saxons were best. But Angles and Saxons had Germanic origins, and Emerson didn’t much care for Germans. So he wrote that, yes, English Anglo-Saxons were superior. But only because they had been influenced by invading Viking—Nordic—blood. (Viking blood apparently didn’t have the same helpful influence on the Irish, even though they invaded Ireland, as well.)

The problem was, in the nineteenth century, Nordic nations were economically poor and seen as backward. Emerson got around that by saying, well, the best Nordics had all gone to England! So—the Nordic nations themselves, like the Irish, were inferior. But Nordic influence on the Anglo-Saxons made the English superior. If you’re dizzy by this time, so am I!

This kind of convoluted rationalization was typical of Victorian-era racism. Emerson’s writings on race were popular and influential. Some of them got woven into the crackpot writings of an Englishmen named Houston Stewart Chamberlain, son-in-law of German composer Richard Wagner. Chamberlain later was called, by some historians, Adolf Hitler’s “John the Baptist.”

Unitarian Universalists like to quote a journal entry, in which Emerson happily referred to our nation as a racial “melting pot,” to suggest that he believed in racial equality. But that’s just proof-texting. Painter notes that Emerson expresses that kind of generosity nowhere else in his writings. Emerson disliked slavery, but saw Africans as inferior. More typical of Emerson, Painter says, is the statement, “The loss/captivity of a thousand negroes is nothing to me.” Blacks, the Irish, Asians—everyone except Emerson’s beloved, Nordic-influenced Anglo-Saxons—were, again, “guano races,” whose worth and dignity were, at best, minimal.

I can write about William Ellery Channing’s cluelessness, but that’s an intellectual exercise. It took Ralph Waldo Emerson to hit me in the belly personally. My great grandfather arrived from Ireland about the time Emerson was at the height of his influence. I’ve read how despised the Irish were in the nineteenth century, but again, that was intellectual, not visceral. I grew up blonde-haired, blue eyed, I’ve always felt “White,” whatever that means. It took the Unitarian Universalist icon, Ralph Waldo Emerson, to remind me that I, too, am descended from “guano.”

Racism is an amorphous thing, and always hungry. It will sooner or later bite everyone who wanders within reach.

There are plenty of reality checks on all this. A layperson such as myself can go at least as far back as a 2003 cover article in Scientific American by geneticists Michael J. Bamshad and Steve E. Olson: “Does Race Exist?” They note that genetic analysis can help categorize people for, say, medical purposes. But usable genetic groupings have nothing to do with what we consider “race.” That is, differences in skin color, hair texture, and some aspects of body shape, involve very few genes out of a whole human genome. It’s quite possible for me to have more genetic material in common with someone whose family origins are in Africa than someone else who, like me, traces their lineage back to the British Isles. Even though they happen to look more like me. There’s far more genetic variation within each “race” than between “races.”

Or as Northwestern University medical professor, Erin Daksha-Talati Paquette, writes in a recent Scientific American blog post, “Racism is Literally Bad for our Health.” Race, she writes, is a study in sociology, not biology. The effects of race and racism are real—and harmful. But they have little to do with inherent biological differences.

From the Roman historian, Tacitus, to Ralph Waldo Emerson, to Nazi racial proclamations, to the latest mass shooting manifesto in the United States, those contrived theories about race are nonsense. Sometimes they are deadly nonsense. But they are nonsense all the same.

Or to put it a different way, you don’t have to get as far into the weeds as Emerson did to participate in racism. Racism isn’t just the belief that one “race” is more intelligent or socially superior to another. It’s the belief, rooted in scientific ignorance, that there are any comprehensive differences between groups of people that can be predicted by skin color or hair texture. Yet significant numbers of supposedly well-educated people still buy into such stereotypes, consciously or unconsciously.

One example is Nobel Prize-winning scientist James Watson. He co-discovered the structure of the DNA molecule in 1953, for which he later received his Nobel Prize. Not incidentally, he was also signatory to the 2003 iteration of The Humanist Manifesto. His career in molecular biology, zoology, and genetics was long and mostly distinguished. But as we see in Emerson, brilliance in one field does not prevent appalling ignorance in another. This can sometimes remain true even though the fields don’t seem all that far apart.

Watson has a history of sexist, racist, and homophobic on-the-record remarks. At a lecture at the University of California at Berkeley in 2000, he hypothesized that thin people were more naturally unhappy than fat people, therefore more likely to be successful. And that melanin, the pigmenting material in human skin, caused dark-skinned people to have stronger sex drives than light-skinned people. One attendee that night, Berkely genetics professor Thomas Cline, summed up the scientific feedback: Watson had “crossed over the line” from being provocative to being downright irresponsible, Cline commented. His talk had consisted of mere conjecture based on racial, social, and fitness stereotypes, rather than tested scientific evidence.

Watson didn’t change—or learn. In a 2007 interview, he insisted that darker “races” were less intelligent and creative than “Westerners.” One English biology professor, Steven Rose, observed that “If [Watson] knew the literature in the subject he would know he was out of his depth scientifically, quite apart from socially and politically.”

Watson has continued to make outrageous statements, even after being removed from multiple teaching and research posts. Through all this, he regularly extols the virtues of “reason,” as though it were a discrete item, to be picked up at will. But multiple observers, more current than Watson on the study of race and genetics, have observed that his statements are an unfortunate combination of a man who likes to create a stir—who also doesn’t know “what on earth he’s talking about.”

This is an important point. A person brilliant in one field, but uninformed in another, can feel as much prejudice as easily as anyone else. All too often, as in Watson’s case, they justify their emotions in the name of “reason.” That is, they use the rhetoric of “reason” to justify a position that derives completely from emotion and social conditioning. Or as science journalist Michael Shermer noted in his book, Why People Believe Weird Things, “Smart people [can also] believe weird things because they are skilled at defending beliefs they arrived at for not-smart reasons.” (Italics in the original.)

Harvard paleontology professor and science writer Stephen Jay Gould’s 1981 book, The Mismeasure of Man, dismantled Watson’s racial assumptions (and also the racially motivated book on intelligence, The Bell Curve,) before they were even written. Gould delved into the history of intelligence testing and showed in detail how, like reason, intelligence was not a single entity, to be measured as a predictor of achievement. He presents a history of attempts to do so which shows how vulnerable even scientists can be to confirmation bias, often based on “racial” assumptions.

“Since biological determinism possesses such evident utility for groups in power,” he writes, “one might be excused for suspecting the it also arises in a political context. . . . I criticize the myth that science itself is an objective enterprise. . . . [S]cience must be understood as a social phenomenon.”

What we learn—or should learn—from science journalist, Michael Shermer, and scientists Jonathan Marks and Stephen Jay Gould, then, is the distinction between scientific research—which is a process—and scientific-sounding proclamations. The latter can, as easily as not, be nothing more than pretentious nonsense. Just as the rhetoric of “reason” gets used to defend opinions that are purely cultural/emotional, the rhetoric of science can also be used to put forth opinions that range from non-scientific to downright ignorant.

One further case in point would be a Princeton bioethics professor, Peter Singer, who sprang to Watson’s defense. In a 2008 article in Free Inquiry magazine, no less, which proudly proclaims its own open mindedness and enlightenment, Singer called for testing to “investigate the possibility of a link between race and intelligence.” He further suggested that those who opposed such testing preferred “ignorance over knowledge.

This was one more stunning display of—clueless—ignorance cloaked in the virtues of “reason.” Not only did Singer ignore existing scientific research on exactly that topic, his judgmental proclamation was nonsense on its face.

As one example, how would Singer even go about testing President Barack Obama, whose mother was Euro-American and whose father was Kenyan? Where would Obama stack up on Singer’s scale between “White” and “Black?” How about Barack and Michelle Obama’s two daughters? How about Tiger Woods? Or millions more people of “mixed” parentage? Into how many categories of whiteness/blackness/etc. would Singer need to divide his subjects even to test them? Would he use the “one drop rule” of the old southern slaveholders? That would say a deal more about Singer than about intelligence or lack thereof in his subjects.

This is what patent, pseudoscientific nonsense looks like in the real world—in a publication that pretends to dedicate itself to “reason.” Yet Singer’s other advocacy against war and poverty and in favor of human rights and realization are well known. One wonders why he would write such an article in the first place. Perhaps out of loyalty to Watson? Or perhaps, attempting to show himself as having a truly open mind, he opened it so much that his common sense fell out? Whatever his motivation, Singer’s proposal is just one more claim that gurgles down the bathroom drain of absurdity when one considers how inapplicable it is in the real world, even if someone were foolish enough to take it seriously.

Watson (and presumably, Singer) were, in part, decrying the problem of poverty on the continent of Africa, claiming that it was incurable because of innate differences between the “races.” But this is more of the kind of ignorance Michael Shermer warns us about in “educated” or “smart” people. Not unlike Ralph Waldo Emerson’s racial theorizing, and once more under the rubric of “reason.”

Economist Paul Collier’s book, The Bottom Billion, among other studies, delves into a long list of complex reasons for poverty in equatorial countries. None of them involves the intelligence of the population.

But that’s cluelessness for you. Channing, Emerson, Watson, and Singer were uninformed about the lives of people in social stations very different from their own. Yet because they had established expertise in one field of study, they foolishly assumed their expertise would transfer into a field in which they had little or no knowledge or insight. They didn’t know. Yet they didn’t know that they didn’t know. Cluelessness yawns before any of us the moment we approach a complex problem in terms of what we think we know, rather than humbly reflecting on the much greater percentage we don’t know.

Or to repeat the wisdom of anthropologist Jonathan Marks: “Sometimes being smart can entail shutting up and not exposing the scope of your ignorance, so that your prejudices are not confused with actual knowledge.”

*Adapted from my forthcoming book, Ahnungslosigkeit: the Education of a Clueless White Man

Leave a Reply