I came of age in the 1960’s, a turbulent decade of civil rights struggle, the Vietnam War, mega-rock concerts, and also iconic assassinations: John and Robert Kennedy, and of course, Martin Luther King.

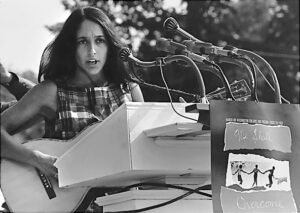

No less emblematic of the ’60’s was the folk music scene, the acknowledged queen and king of which were singer-songwriters Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. Baez was already a star when they met. Her tremulous soprano voice turned every note into an appeal from heart to heart.

No less emblematic of the ’60’s was the folk music scene, the acknowledged queen and king of which were singer-songwriters Joan Baez and Bob Dylan. Baez was already a star when they met. Her tremulous soprano voice turned every note into an appeal from heart to heart.

From the time they met, Baez recognized Dylan’s prodigious talent: “already a legend,” she later wrote of him. Five decades later, of course, his lyrical innovations garnered him a Nobel Prize.

She took him under her wing professionally even as she fell head-over-heels in love with him emotionally. She recorded his songs, providing early exposure. She took him on tour with her, sang duets with him, defended him when some audiences booed him for his own harsh singing voice.

They became colleagues, then lovers. One suspects, however, that his feelings toward her were never as straightforward as her passion for him. He was ambitious. Despite all the professional help she gave him, as one ancient sage has been quoted, “When two ride the same horse, only one can ride in front.” Dylan wanted to be in front. By 1965, it was plain that he wanted to be “in front” more than he wanted her.

The1965 motion picture, Don’t Look Back, documented their breakup. The film was conceived around Bob Dylan’s first concert tour through England. In part because he resented the onscreen exposure she was receiving, Dylan “ghosted” Baez in a manner still termed “callous” by music historians. During the second half of the tour (and the movie), he treated her as if she were invisible.

They remained in touch. A generation would pass before Baez would admit it, but she carried a torch for him for years: a stew of love, hurt, and resentment with which any jilted lover can identify. It took Dylan forty years to half-heartedly acknowledge the shoddy way he had treated her.

He did still telephone her occasionally, usually out of the blue. One call came in 1974. He wanted to read her the lyrics of a song he had just written. That strikes me as such a “guy” thing to do. He had moved on, he didn’t desire her any more in the romantic sense. But he still wanted her to validate his genius. He called her, smugly expecting her to oblige. That’s just my assessment. Dylan never recorded his emotions about the call.

We know exactly how Joan Baez felt, though, because as soon as she hung up, she wrote a song about it: “Diamonds and Rust.” The sweet melody and breezy lyrics take the edge off resentment so pointed, the song was later covered by those masters of pain and resentment, the heavy metal band Judas Priest! Other heavy metal bands followed suit, trimming the lyrics so that the heavy metal version is about betrayal in general, not one particular couple.

Baez denied for a long time that the song was about Dylan. But no one could listen closely lyrics and think otherwise. “Ten years ago, I bought you some cufflinks,” she sings. Christmas, 1964: one can picture her, lingering over them in a jewelry store, picking just the right ones. “You bought me—something.” Some generic gift into which little thought was applied, and of which little memory remains. But “We both know what memories can bring. They bring diamonds and rust.” That is, ecstatic moments—the diamonds. But also the rust, the lingering hurt, not just from being discarded, but also from realizing that their relationship had been unequal from the beginning.

The final verse is particularly poignant. Once again, it couldn’t have been about anyone except Dylan:

“Now you’re telling me that you’re not nostalgic.”

[Really? After all, he was the one who called her out of the blue, seeking her validation, cocksure she would provide the bit of mothering he sought.]

“You’re telling me you’re not nostalgic.

Then give me another word for it, you who are so good with words,

And at keeping things vague.”

There’s some hurt for you. Dylan, so “good with words,” adept also at “keeping things vague.” Because after being so callously dumped, Joan Baez realized that, apart from what he wanted from her—he had never adored her the way she adored him.

She finishes with:

“‘Cause I need some of that vagueness now,

It’s all come back so clearly. Oh, I loved you dearly.

And if you’re offering me diamonds and rust,

I’ve already paid.”

Joan Baez finally did admit, decades later, that she had loved Bob Dylan dearly. And that she hurt for a long time. And that the song was, indeed, about him.

What’s important for us, though, is that her heartbroken specificity captures something universal in unequal relationships. Vagueness—what Henry Nelson Wieman might call “evasion”—is a tool by which we comfortably maintain unequal relationships, cultural as well as romantic.

That’s why I try to discuss marginalization in terms of experience, rather than theory. Because, again, if we keep the discussion at a theoretical enough level, theory also allows us to keep it comfortably vague.

To honestly examine unequal relationships, we need to pierce through vagueness. We need to experience the discomfort—the “anxiety”—that comes of “emptiness”—in The Heart Sutra sense—openness to non congenial reality.

This calls forth the courage to use precise words: homophobia, transphobia, Islamophobia, ableism, racism, white privilege, and that overarching, much-avoided term, white supremacy culture. That brings us to that even less comfortable term for anxiety and discomfort provoked when our vagueness gets challenged: white fragility.

Back to Joan Baez’s lyric: “Now you’re telling me that you’re not . . . .” Here let us finish the line with any of the uncomfortable words I mentioned above. Or let me add another word for the incuriosity by which vagueness and injustice thrive: cluelessness.

“Then give me another word for it,” she charges, We—that is we Unitarian Universalists—“who are so good with words,

And at keeping things vague.”

If we can keep anyone from naming it, we don’t have to deal with it.

*Adapted from the Introduction to my upcoming book, Ahnungslosigkeit: the Education of a Clueless White Man

Leave a Reply